Santi Monastery is created in the spirit of the Buddhist Forest Tradition. For us, the forest (or ‘bush’ as we say in Australia) is the temple. We remember that the Buddha went forth to the forest, practiced in the caves and wilderness, and was Awakened beneath the Bodhi Tree.

In the early years of Buddhism, all monastics lived in the forest. Gradually, there was a drift towards more settled monasteries in the villages and cities, but the forest life has always been there. Throughout history, whenever Buddhist monasticism becomes too domesticated and safe, there always arises a ‘back-to-the-roots’ revival of the forest contemplative life. In modern Thailand, Sri Lanka, Burma, Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan, and elsewhere one can find monasteries and hermitages tucked away in secluded regions, providing quiet havens for contemplation and solitude.

The most vital modern resurgence of the forest tradition was in Thailand. The modern forest tradition was made possible by the reforms initiated in the mid 19th Century by the future King Mongkut (1804-1868). During his 27 years as a monk, he became highly critical of Buddhism as it was then practiced in Thailand. He believed that it was full of magic and superstitions that had nothing to do with Buddhism, and was particularly critical of those who mindlessly passed down the teachings according to what their teachers said, without any understanding of the Buddha’s own words. He undertook an intensive study of the Pali Canon, which he believed to contain the earliest teachings of the Buddha. Using modern text-critical methods, he attempted to divest Buddhism of its harmful and irrational accretions, and to return to a pristine form of original Buddhism. These inquiries became the foundation for the reformist Dhammayut order.

However, in its endeavour to construct a Buddhism on modern, rational lines, Mongkut’s reforms tended to deprecate meditation. Indeed, it was commonly believed, and still is today, that meditation was useless, as the lofty spiritual attainments spoken of in the ancient texts were believed to be no longer accessible in our ‘degenerate age’.

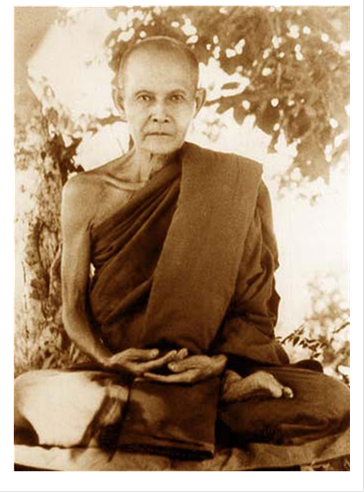

The renowned meditation master Ajahn Mun (1870-1949) was not content with this ideology, and he resolved to test it for himself. He developed a practice emphasizing austerity, strict discipline, and orthodox meditation practice, dispensing with the magical and superstitious elements that then dominated Thai mysticism. Rejecting the purely scholastic emphasis of the reformist Dhammayut order in the early 20th Century, Ajahn Mun insisted that the path to realization of the Dhamma was as open and relevant today as it was in the Buddha’s. While the basic doctrinal framework that he used was informed by the rationalist conclusions of Mongkut, Ajahn Mun strongly emphasized the primacy of direct experience over mere book learning. His radical, uncompromising approach led to years of conflict with the central authorities, who preferred their monks tame and civilized. Ajahn Mun lived many years of his life as a Dhutunga monk, living and meditating in the forests of Thailand, often in solitude, though later, often followed by a band of his monastic disciples. In the intensity of his gaze, as preserved in the few photographs of his that exist, it is easy to understand how he is regarded by many in Thailand as an arahant, or fully Awakened master.

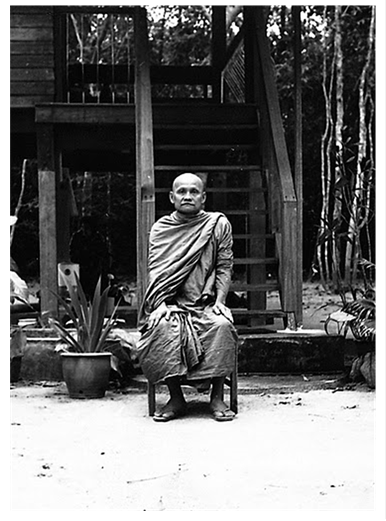

Ajahn Mun had many talented disciples who established their own monasteries. Two of the best known were Ajahn Maha Boowa and Ajahn Chah (1918-1992). Ajahn Chah spent his formative years wandering around Thailand, staying in forests and monasteries, learning from many different teachers, but always dedicated to meditation. Eventually he settled down near his home town and set up the monastery Wat Nong Pa Pong. While Ajahn Mun emphasized solitary, dedicated striving, Ajahn Chah saw how such practice tended to become dependent on the strength of charismatic teachers, and when those teachers passed away, the practice fell apart. He changed the approach found in the Ajahn Mun circles to give more emphasis to the Sangha over the teacher.

Ajahn Chah became extremely popular as a teacher, and the organization he founded is now by far the largest group of forest monasteries in Thailand. He attracted many Western disciples, who set up the first forest monastery in Thailand for English speaking monks, Wat Pa Nanachat, in 1975. Subsequently, several Wat Pa Pong branch monasteries were established internationally.

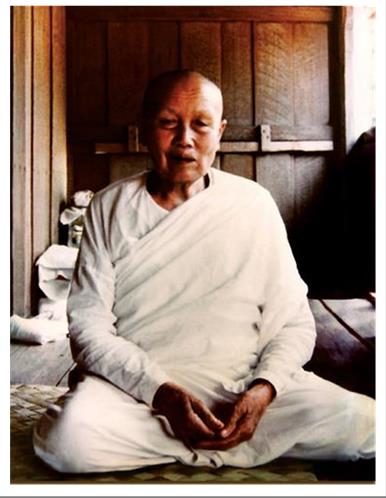

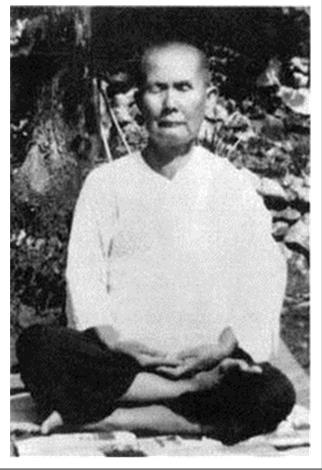

There were also two well-known and accomplished female practitioners in the Thai forest tradition during this same period – Mae Chee Kaew (1901-1991) and Upasika Kee Nanayon (1901-1978).

Mae Chee Kaew was a disciple of Ajahn Mun, whom she met when she was a young girl and received direct meditation instruction from him. He saw her spiritual potential and continued to support her with teachings up until his death. Later, she became a student of Ajahn Maha Boowa, who was significant in helping her develop further in her practice and reach fruition. Her life story and spiritual journey has been made more well-known through a recent publication, and lends great inspiration for women on the path.

Upasika Kee was a ‘lay’ eight-precept practitioner who retired to a simple forest setting to develop the path of meditation, supported by family and like-minded practitioners. It seems she was predominantly self-taught through the study of suttas and texts of Thai meditation masters. The forest property developed into a lay meditation centre and Upasika Kee became “arguably the foremost woman Dhamma teacher in twentieth-century Thailand” (Thanissaro Bhikkhu). The forest tradition of 20th Century Thailand has been one of the most fascinating and important forces in the development of modern Buddhism, both in the East and West.